A modern glass addition to the Lovejoy Wharf property in Boston added square-footage while creating a bold waterfront statement. Photo courtesy of TAT

For developers and owner-operators throughout New England, adaptive reuse has long proven a cost-effective, sustainable and market-responsive means of generating new housing units, creating successful mixed-use communities and preserving our region’s architectural history.

While ideal candidate structures may be a century old or more, time does not stand still for any development team, and the realities of revitalization are constantly evolving. As architects engaged in dozens of preservation, renovation, and conversion initiatives, our firm, The Architectural Team, has identified several trends that are shaping the adaptive reuse sector today. These considerations can help project teams plan and carry out more effective redevelopments.

Value Added to Something Old

As new development sites become more challenging to find across New England, combining adaptive reuse with new construction offers an effective way to utilize existing building assets within already built-up neighborhoods. Preserving the streetscape and ties to the community’s past and enhancing a site’s value with additional or larger residential units or space for mixed uses have become strategic tactics.

Developers often find that this blending of old and new also helps broaden a multifamily property’s appeal to diverse psychographic audiences. Some residents, for example, may prefer the more efficient layouts possible with new construction, while others may enjoy the irregular and unique floor plans of a historic conversion.

Especially with landmarked buildings, project teams must keep in mind that many local and national regulations require a clear stylistic or even structural differentiation between the original building and any new addition. For example, TAT’s conversion of the historic Bourne Mill complex in Rhode Island utilized contrasting materials when a courtyard was cut into the existing building footprint. Existing beams were wrapped, protected with metal panning and the new exterior wall included fiber cement panels and corrugated metal siding as the finish. The newer materials complimented the existing granite walls, but clearly marked them as distinct from the original building fabric.

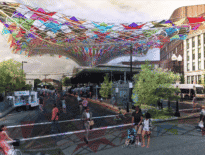

In our experience, the necessity of creating this hard edge also opens the door for creative architectural expressions that can serve as differentiators in competitive markets. At the Lovejoy Wharf development in Boston, a contemporary glass addition forms a bold statement above the original masonry structure. This strategic alteration by TAT’s team allowed the project to meet guidelines while significantly increasing square footage and generating an instantly iconic waterfront presence. A similar design solution was employed at 100 Shawmut, a residential conversion in Boston’s South End that wraps a historic warehouse structure with a glazed addition – effectively doubling the property’s size.

Achieving High Performance

For decades, housing leaders have known that adaptive reuse is a sustainable building practice, because it eliminates the carbon emissions and environmental waste of new construction. But as energy codes become stricter, older buildings will need to perform to the same high-performance level as their contemporary counterparts.

The implications for adaptive reuse initiatives may seem daunting, but architects see it as a compelling opportunity. For example, while it’s notoriously difficult to insulate the brick walls common in older structures, extensive repointing and the specification of historically matched, high-performance windows can dramatically improve envelope performance. Many older structures also have interior plaster wall finishes, which preservation authorities have allowed our design teams to insulate on numerous projects, such as Curtain Lofts and Knitting Mill Apartments in Fall River, and Livingston School Apartments in Albany, New York.

When it comes to building systems, recent advances also bode well for the long-term viability of historic conversions. Electrification, for instance, is a growing trend and even a mandate in certain cities and towns. Project teams exploring this approach are realizing that it’s fairly straightforward to implement fully electric systems in the adaptive reuse process – as TAT is doing at Stone Mill, the all-electric residential conversion of a landmark structure in Lawrence.

On-site geothermal power generation is another promising trend that offers the potential for nearly complete carbon neutrality. Currently an expensive proposition, we’re seeing evidence that costs are beginning to decrease, and in fact we’re incorporating geothermal facilities in the historic adaptive reuse of the Ropewalk in the Charlestown Navy Yard.

The large footprints of mill buildings and other former commercial and industrial structures lend themselves particularly well to solar arrays without much need for structural reinforcement, since these properties were originally constructed to take very heavy loads. Sightline analysis can be used to locate the solar arrays so that they aren’t visible from the ground, preserving historic building profiles. Additionally, new arrays are so low-profile and compact that it isn’t an issue for these old brick mills with flat or shallow pitched roofs. Our team currently has eight adaptive reuse projects in the works with solar arrays, and with grants available to developers, we expect to see more.

Midcentury Modern Becomes ‘Historic’

For those in the development and design of multifamily communities, the phrase “historic landmark” tends to conjure images of 19th or early 20th-century structures. But, as buildings from the 1950s, 1960s and later begin to fall within the eligibility period for historic designations, project teams will have to learn to adapt to stringent guidelines.

In some ways, this mode of renovation and adaptive reuse is simpler than it would be with a more classically historic structure. Project teams will find less of the challenging-to-restore exposed decking or masonry, and more steel-encased concrete. These newer structural systems bring benefits for conversion work, including greater ease of adding insulation to help projects meet energy goals.

Scott Maenpaa

On the other hand, whereas many old industrial and commercial buildings were essentially a blank slate in terms of interior decoration and finishes, midcentury or newer structures are more likely to have interior detailing that contributes to designated historic character and therefore requires restoration and preservation. Project teams will need to pay close attention to original plans and documentation, and collaborate with preservation authorities in assessing existing interior conditions. Our design teams often find creative ways to restore and preserve the original details, such as etched marble trim or beautiful midcentury built-in clocks, that allow the redevelopment to meet guidelines for landmark work. In any project seeking historic tax credits or related funding mechanisms, this is especially important.

Finding success with adaptive reuse initiatives is about paying attention to these details – and integrating this focus with a broader understanding of the trends and drivers impacting this market sector as it continues to evolve. Design and development teams agile enough to pursue these trends are gaining ground throughout New England – from blending renovation with new construction, and from emphasizing energy efficiency and taking on newly historic properties – will add outsized value to their communities for years to come.

Scott Maenpaa is a project manager with The Architectural Team, Inc. of Chelsea.

|

|