Jordan Zimmermann

Urban heat islands plague our built environment. These man-made phenomena absorb heat and raise the surrounding temperature, contributing to the public health dangers caused by a warming planet and limited mitigation efforts. In fact, heat-related illness is responsible for more U.S. deaths than any other weather-related cause and, unlike flooding, is virtually invisible. It can be difficult to discern the threshold at which an emergency is triggered for a geographic area or for an individual.

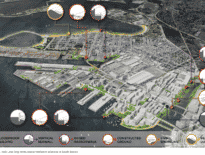

Last year, Urban Land Institute convened a study of urban heat islands and prepared a report called, “Living with Heat.” Teams of local real estate professionals and community stakeholders examined several Greater Boston neighborhoods that are home to high numbers of urban heat islands: East Boston, Lower Roxbury, Somerville and Chelsea/Everett. Each site group focused on design and programming solutions, such as increasing open space, providing cooling centers for the community, redesigning buildings and rezoning strategies.

Larissa Belcic, a landscape architectural designer, was keynote speaker for the event and emphasized the need for a “climatic parfait,” as opposed to a one-size-fits-all approach to protect people from extreme urban heat. The ULI study group sought multiple solutions tailored to each particular site. It is worth noting that many of the heat mitigating strategies overlap with solutions that mitigate flooding, which represents an exciting opportunity to solve more than one issue.

The study underscores not just the threats to urban residents from a warming planet, but also the social and racial injustice inherent in locations with urban heat islands.

The sites ULI studied are largely populated by people who are low-income and non-white. For example, East Boston’s population is 53 percent Hispanic; Lower Roxbury is 51 percent Black. Only Somerville is a majority white community, but it is also the most densely populated city in Massachusetts.

The study sites are largely home to vulnerable populations, many of whom lack air conditioning in their homes, access to public transportation within a short distance, access to green space or shade for relief on hot days. Not surprisingly, people living in these neighborhoods tend to have asthma or other preexisting conditions, which make exposure to extreme temperatures more dangerous.

White Roofs and Pop-Up Parks

One of the major takeaways for the study group was the number of options that exist to mitigate the effects of urban heat islands. The East Boston team proposed implementing a “cool roof program,” based on Philadelphia’s Cool Roof law. When property owners replace their asphalt roof with a white, reflective roof, it improves the interior temperatures of a home and offers the potential, when replicated across many properties, to reduce heat in the overall neighborhood.

For Lower Roxbury, the team proposed a summer pop-up park, inspired by the city of Boston’s H2Go water trailers. The pop-up park not only could provide free cooling opportunities, it can also improve community engagement during summer months. Education about the risks posed by extreme heat could be part of the pop-up park programming, so residents and businesses can better prepare themselves for more hot days in the future.

Inspired by Larissa Belcic’s presentation, the Somerville team sought a multi-layered approach which included daylighting the historic Millers River. Taking advantage of breezes off of the river will naturally cool the adjacent site and provide relief for the users from extreme heat. The Somerville site also includes a highway underpass, which would be programmed for public use in the shade.

The Chelsea/Everett proposed a program to engage existing businesses in implementing green practices. Businesses with large lots and roof areas could be encouraged to install green or blue roofs. Finding creative ways to cool these spaces could also serve as a source of civic pride and unity for the Chelsea business community, which includes the city’s produce center and long line of idling trucks.

As these concepts demonstrate, the dangerous effects of urban heat islands can be reduced with a concerted effort involving the real estate, design and engineering fields – and a commitment from local governments. Such steps will improve overall health and help mitigate existing racial and social inequities.

Jordan Zimmermann is a tenant design and coordination manager at New England Development Corp. and co-chair of the ULI Boston/New England Climate Resiliency Committee.

|

|