A 144-acre section of Dorchester Avenue in South Boston could support up to 8,000 housing units by giving developers incentives to set aside residences for middle-class households.

A mile-long corridor lined with warehouses, machine shops and self-storage facilities in South Boston could give way to mixed-use developments and residential towers rising up to 30 stories under a draft land-use plan.

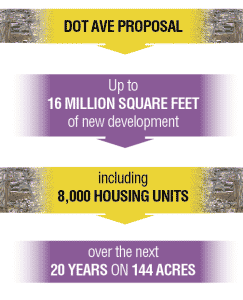

The South Boston Dorchester Avenue study sees potential for up to 16 million square feet of new development including 8,000 housing units over the next two decades on 144 acres between the Broadway and Andrew MBTA stations. The product of a 10-month study and community review, the plan will go to the Boston Redevelopment Authority board of directors for approval this summer.

Developers could get density bonuses for taller buildings in exchange for providing more middle-income housing and other benefits such as open space in a neighborhood with no public parks. There’s also potential for up to 7 million square feet of commercial and industrial space, including green labs and makerspaces in podiums beneath residential towers overlooking the MBTA tracks.

The study anticipates that the forces of gentrification that have reinvented other portions of South Boston and South End will transform the neighborhood, which currently has 1,200 housing units.

The new zoning would replace a permitting patchwork that allows developers to seek exemptions through planned development areas and zoning variances, contributing to a hodgepodge of uses and densities, said Dom Lange, cofounder of Broadway Village Real Estate in South Boston.

“We’ll see how much happens during this economic cycle but regardless, it’s great,” Lange said. “When somebody is ready to develop that land, [the plan states,] ‘Here’s what you can do.’ The South Boston community process has been exhausting because there’s just no clear parameters of what you can do.”

Luxury Housing Pops Up Amid Industry

That hasn’t stopped forward-thinking developers from scooping up residential sites.

Milton developer Thomas Broderick Jr. and Kingston architect Timothy Russell received approvals in 2014 for an $8.5 million, 33-unit luxury condo development at 488 Dorchester Ave. A trucking company warehouse previously occupied the 0.4-acre site.

To build the 4-story, 49,900-square-foot project, the developers needed 12 separate waivers from the Zoning Board of Appeals in such categories as excessive floor area ratios, excessive building height and insufficient off-street parking.

Scheduled to open this summer, the complex is listing a 1,459-square-foot unit for $965,000, or $661 per foot.

In April 2015, DJ Properties and Core Investments of Boston submitted plans for 656 multifamily units and nearly 100,000 square feet of retail space on a 5-acre cluster of industrial parcels at the corner of Old Colony Avenue and Dorchester Street.

In April 2015, DJ Properties and Core Investments of Boston submitted plans for 656 multifamily units and nearly 100,000 square feet of retail space on a 5-acre cluster of industrial parcels at the corner of Old Colony Avenue and Dorchester Street.

The developers are fine-tuning the mix of units to include more middle-class housing in response to public comments, BRA spokesman Nicholas Martin said.

Core Investments’ David Pogorelc also is listed as manager of DotAve Ventures LLC, owner of one of the neighborhood’s largest vacant parcels at 511 Dorchester Ave., and one that would stand to be transformed by the BRA vision. DotAve Ventures acquired the 6.2-acre site in April 2014 for $13.4 million.

The conceptual study would extend Ellery Street from the rear of Andrew Station through the 6.2-acre DotAve Ventures site, creating a broad “green” boulevard lined with high-density development that runs parallel to Dot Ave. The idea for the new road emerged because of the width of the building lots between Dorchester Avenue and the MBTA tracks, Lange said.

Thomas Palmer, a spokesman for Core Investments, said the owners are planning a mixed-use project including commercial space on the site.

The push for more housing dovetails with Mayor Martin Walsh’s goal of adding 53,000 residential units citywide by 2030 to help moderate the region’s housing costs.

J.P. Plunkett, a principal with Dorchester-based commercial brokerage Red Dome Realty, said the cost benefits of industrial conversions will diminish as sites for service businesses become ever more scarce in the city.

“People who take a deep breath and don’t hop on this fancy residential-hotel train are going to be ecstatic with what their industrial space is worth as industrial real estate,” Plunkett said. “If they go through the analysis of redevelopment time and construction risk, what spits out of the formula is that keeping things as old-fashioned industrial is just as profitable with no time elapsed or risk.”

Support For More Housing In Taller Structures

Walkable streets, middle-class housing and inviting open spaces landed high on the wish lists mentioned by residents during a series of community meetings hosted by the BRA beginning in July 2015.

“There was a strong desire for creating more middle-income housing, a lot of open space, and creating an improved street experience,” said Viktorija Abolina, a BRA senior planner. “Currently there aren’t many connections, there are very narrow sidewalks and absolutely no trees in the study area.”

Developers have begun buying up industrial parcels near Andrew Square to build luxury condos with asking prices topping $600 per square foot.

To accommodate more housing, a community consensus favored zoning for taller mixed-use buildings near the two subway stations. On the west side of the district facing the MBTA tracks, space would be zoned for “21st-century industrial uses” such as renewable energy companies and commercial kitchens beneath residential towers. The side fronting on Dorchester Avenue would be reserved for residential and commercial uses, but not industrial.

As-of-right building heights would start at 45 feet throughout the district but developers could build as high as 300 feet under density bonuses. Priorities were given to preserving key view corridors, and designing projects to avoid the uniform wall-like appearance of recent development in the Seaport, said Lara Merida, the BRA’s deputy director for community planning.

The Next Frontier?

National Development led the conversion of the former Boston Herald property in the South End into the Ink Block project including housing, a Whole Foods Market and an AC By Marriott hotel. More developers are following its lead, with The Abbey Group of Boston preparing to acquire the Boston Flower Exchange on Albany Street for a large residential and tech office development. A partnership of Rubenstein Properties and Nordblom Co. filed plans in late May for a 230,000-square-foot office building atop a parking garage they own at 321 Harrison Ave.

The Dorchester Avenue corridor shares many characteristics as South End, such as walking distance to transportation, dining and shopping, said Ted Tye, a partner with National Development.

“I see that area as being the next frontier,” he said. “What we’re seen in Boston fairly recently is the really rapid transformation in timeframes we’ve never seen before in the history of the city. They’re developing in three to five years, not 30 years or 50 years.”

Assembling multiple parcels in an area still dominated with working businesses is the limiting factor.

“No one wants to see business completely chased out of the city, and we have to find ways that they’re accommodated as well,” Tye said.

Approximately 250 businesses call the study area corridor home, from gyms and self-storage warehouses to plumbing suppliers and print shops. Businesses comprise about 60 percent of the land area in the study.

There’s even a few small office buildings that are attracting a look from companies priced out of downtown Boston, said Justin Dziama, a vice president at Avison Young. Traditionally, their next stop would be North Quincy.

But Dot Ave could become an attractive alternative if it’s built out with the right mix of uses and thoughtful transportation upgrades such as bike lanes and Hubway stations, Dziama said.

“This is obviously closer to Boston. It can create its own little ecosystem,” he said. “The question is how to do it the right way.”

|

|